How I built a minimal-knowledge sync for WorkLedger

A local-first digital notebook

A bit more than a week ago, I came across the blog post Using an engineering notebook. I personally love notebooks and use... too many of them. My only issue has always been that when my brain is on fire, my handwriting is not neat enough, it's not structured enough, and it helps me to note things down, but it always feels like I could be faster by text-to-speech or keyboard typing.

Now there are moments of silence of course, when I can sit down with a cup of coffee and map out a feature or thought in my head. For that, I don't think any digital device will ever come close to simple pen and paper.

Nevertheless, the time was ripe to "Build it yourself". I am always inspired by Excalidraw. I can open it, don't need an account, draw to my heart's content, and then save the finished drawing as a PNG to my local hard drive and take it anywhere. I wanted to build something seamless like that for writing. Hence, WorkLedger was born.

The landing page gives you a nice feature overview.

Shout out to BlockNote for offering a superb text editing experience.

I thought to myself: Local first is great, I will never need sync. Until I left the house on a Friday to bring my kids to skating lessons, work still ruminating within me, and I thought: Let's get this down on "paper" so I don't forget my thoughts. I opened WorkLedger on my iPhone and saw - nothing. Obviously a new session means new data. Argh. I had to implement sync.

The birth of sync ID

I started using Mullvad VPN this past year and was utterly confused by their lack of... account? I couldn't find a deep dive into this, all I have as an explanation is this blog post from 2017.

I got inspired though: What if I had a button which can generate a sync ID, and with that, I can - sync? That's it. No password, no complicated setup. And I want to copy/paste this sync ID to my devices where I need it. And somehow, the server doesn't even know this id, but still can give me my associated entries.

The core trick: domain separation

The core question is: If the server never sees this magic id, how does it know which entries belong to me?

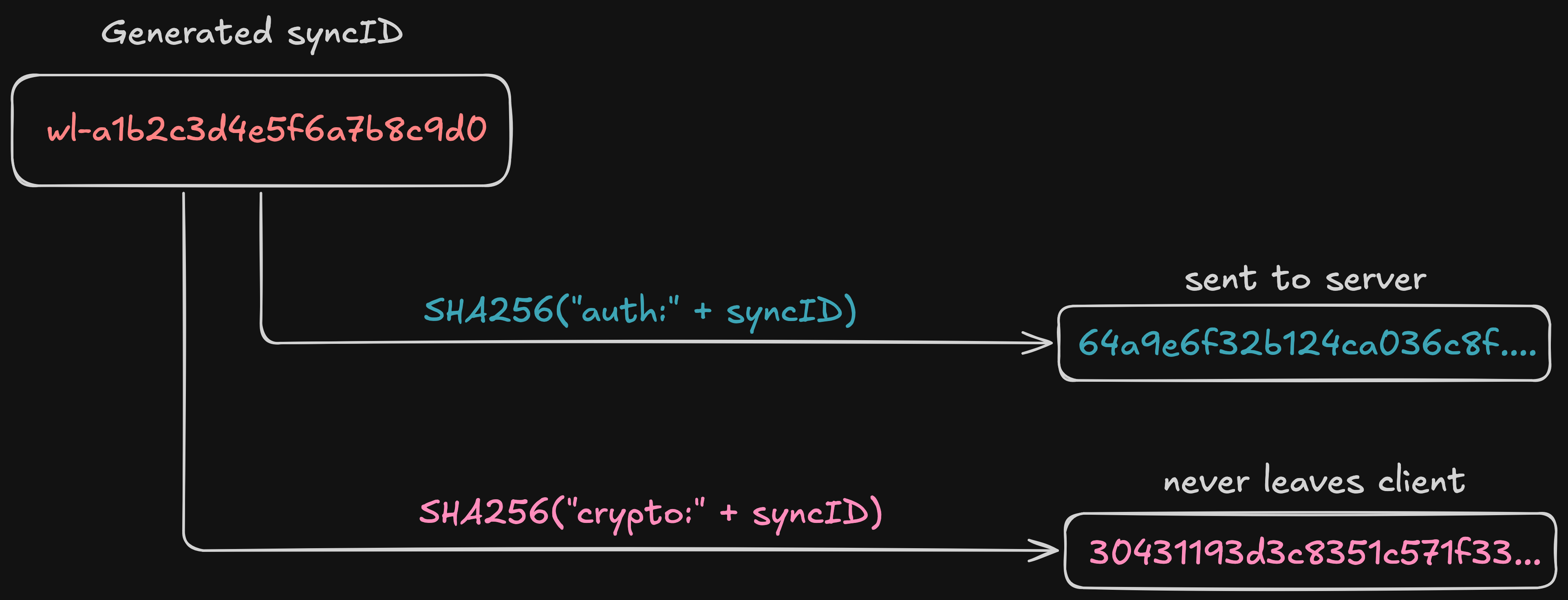

The answer is that one string becomes two different strings through a one-way process. Given a sync ID like wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0, I derive two separate values from it:

This is called domain separation. The prefixes auth and crypto ensure the two hashes are computationally unrelated — knowing one reveals nothing useful about the other.

The auth token goes to the server as an X-Auth-Token header. The server uses it to identify your account and look up your entries. But because it is a SHA-256 hash of a sync ID (not the sync ID itself), the server cannot reverse it. And because the crypto seed uses a different prefix, the server cannot derive the encryption key either.

This is how it looks in my crypto.ts file:

async function sha256Hex(input: string): Promise<string> {

const encoded = new TextEncoder().encode(input);

const hash = await crypto.subtle.digest("SHA-256", encoded);

return Array.from(new Uint8Array(hash))

.map((b) => b.toString(16).padStart(2, "0"))

.join("");

}

export async function computeAuthToken(syncId: string): Promise<string> {

return sha256Hex("auth:" + syncId);

}

export async function computeCryptoSeed(syncId: string): Promise<string> {

return sha256Hex("crypto:" + syncId);

}The sha256Hex function uses the Web Crypto API, which is available in all modern browsers, so I don't even need to import any npm modules for it.

Generating the sync ID

The sync ID is generated client-side from 10 random bytes, giving 80 bits of entropy.

A byte can hold any value from 0 to 255 — that is 256 possibilities. Since each bit doubles the possibilities and 2⁸ = 256, one byte equals 8 bits of entropy. Ten random bytes means 10 × 8 = 80 bits.

For reference:

- A typical password might have 30-50 bits of entropy (guessable)

- 80 bits is in the "nation-state can't brute-force this" range

- 128 bits is the standard target for symmetric cryptography

export function generateSyncIdLocal(): string {

const bytes = crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(10));

const hex = Array.from(bytes)

.map((b) => b.toString(16).padStart(2, "0"))

.join("");

return `wl-${hex}`;

}The result looks like wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0. The wl- prefix is cosmetic - it makes the string recognizable as a WorkLedger sync ID when you paste it between devices.

80 bits of randomness means there are roughly 1.2 × 10²⁴ possible sync IDs. For any realistic number of users — say, 10 million accounts — the probability of a collision is vanishingly small.

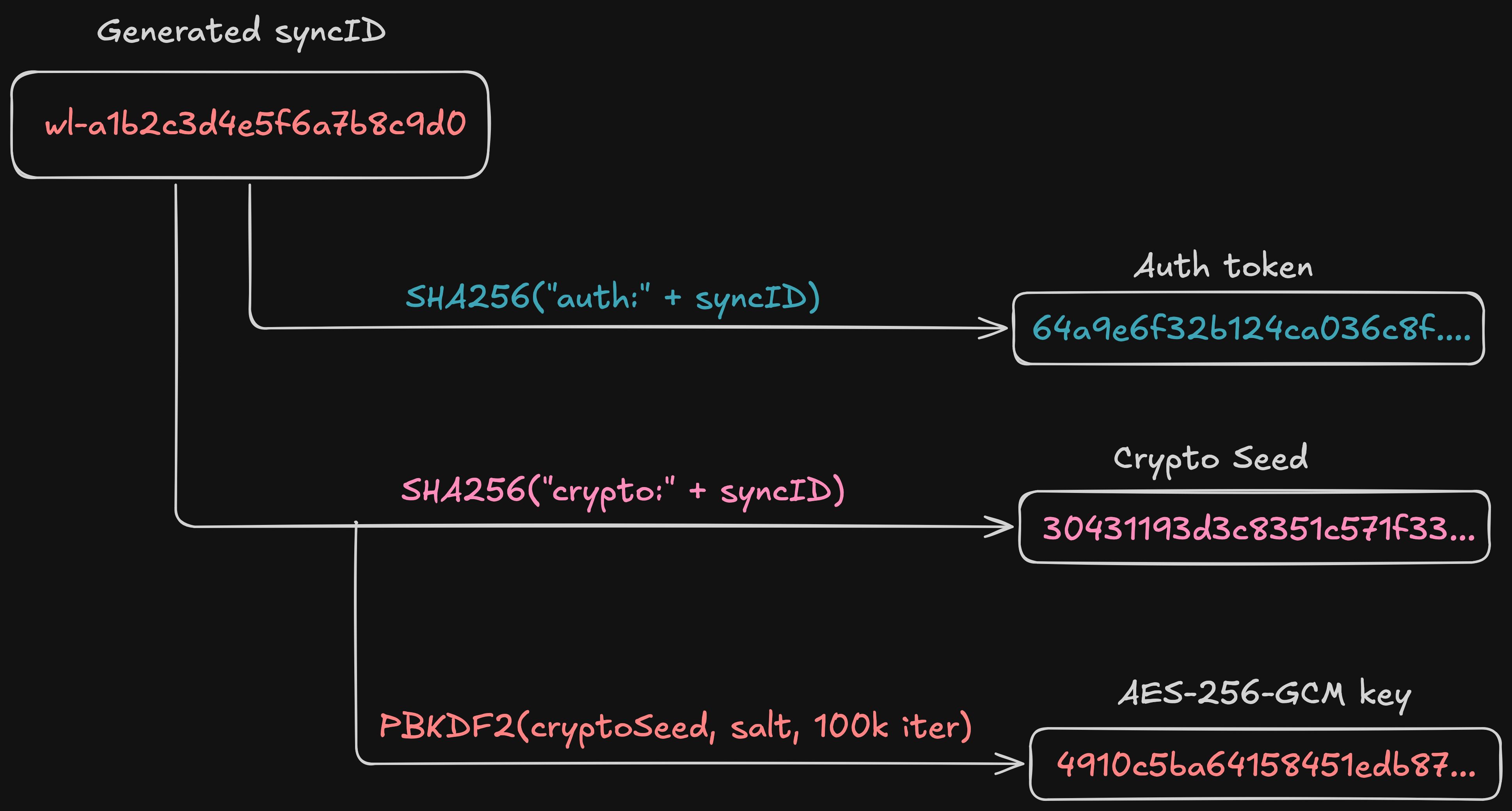

From crypto seed to encryption key

The crypto seed alone is not the encryption key. It goes through one more transformation: PBKDF2 key derivation with a server-provided salt.

When you create an account, the server generates 16 random bytes as your salt and sends it back. This salt is stored alongside your auth token in the server database. Every device that connects with the same sync ID gets the same salt, which means every device derives the same encryption key.

const PBKDF2_ITERATIONS = 100_000;

export async function deriveKey(syncId: string, saltBase64: string): Promise<CryptoKey> {

const cryptoSeed = await computeCryptoSeed(syncId);

const encoder = new TextEncoder();

const salt = Uint8Array.from(atob(saltBase64), (c) => c.charCodeAt(0));

const keyMaterial = await crypto.subtle.importKey(

"raw",

encoder.encode(cryptoSeed),

"PBKDF2",

false,

["deriveKey"],

);

return crypto.subtle.deriveKey(

{ name: "PBKDF2", salt, iterations: PBKDF2_ITERATIONS, hash: "SHA-256" },

keyMaterial,

{ name: "AES-GCM", length: 256 },

false,

["encrypt", "decrypt"],

);

}The output is an AES-256-GCM key - a symmetric key that both encrypts and decrypts. PBKDF2 with 100,000 iterations makes brute-force attacks against weak sync IDs expensive, though with 80 bits of entropy the sync ID itself is already computationally infeasible to guess.

The full derivation chain looks like this:

Encrypting entries

With the key derived, each notebook entry gets encrypted before it leaves the device. I split each entry into two parts: the content payload that gets encrypted, and minimal metadata that stays in plaintext.

export async function encryptEntry(key: CryptoKey, entry: { ... }): Promise<SyncEntry> {

const payload = {

dayKey: entry.dayKey,

createdAt: entry.createdAt,

updatedAt: entry.updatedAt,

blocks: entry.blocks,

isArchived: entry.isArchived,

tags: entry.tags ?? [],

isPinned: entry.isPinned ?? false,

signifier: entry.signifier,

};

const plaintext = JSON.stringify(payload);

const encryptedPayload = await encrypt(key, plaintext);

return {

id: entry.id, // plaintext — server needs for dedup

updatedAt: entry.updatedAt, // plaintext — server needs for conflict resolution

isArchived: entry.isArchived, // plaintext — server needs for filtering

isDeleted: entry.isDeleted, // plaintext — server needs for deletion markers

encryptedPayload, // opaque blob

};

}The content fields — your actual writing (blocks), your tags, your date organization (dayKey) — all go into the encrypted blob. The server gets only an opaque base64 string.

The metadata fields stay in plaintext because the server needs them for operational purposes: id for deduplication, updatedAt for last-write-wins conflict resolution, isDeleted for soft-delete markers.

The encryption itself uses AES-256-GCM with a random 12-byte initialization vector (IV) prepended to the ciphertext:

export async function encrypt(key: CryptoKey, plaintext: string): Promise<string> {

const encoder = new TextEncoder();

const iv = crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(12));

const ciphertext = await crypto.subtle.encrypt(

{ name: "AES-GCM", iv },

key,

encoder.encode(plaintext),

);

const combined = new Uint8Array(iv.byteLength + ciphertext.byteLength);

combined.set(iv, 0);

combined.set(new Uint8Array(ciphertext), iv.byteLength);

let binary = "";

for (let i = 0; i < combined.length; i++) {

binary += String.fromCharCode(combined[i]);

}

return btoa(binary);

}The loop builds the binary string one character at a time instead of using String.fromCharCode(...combined) with a spread operator — spreading passes every byte as a separate function argument, which blows the call stack for entries larger than ~64KB.

AES-GCM is an authenticated encryption scheme. It provides not only confidentiality but also integrity — if anyone tampers with the ciphertext, decryption fails. This matters because the server could theoretically modify the encrypted blobs, and AES-GCM ensures you would detect it. Note that AES-GCM only authenticates the encrypted payload itself — the plaintext metadata fields (id, updatedAt, etc.) travel outside the encryption envelope and are not integrity-protected.

A fresh random IV for every encryption operation means that encrypting the same entry twice produces different ciphertext, preventing identical content from producing identical blobs across pushes.

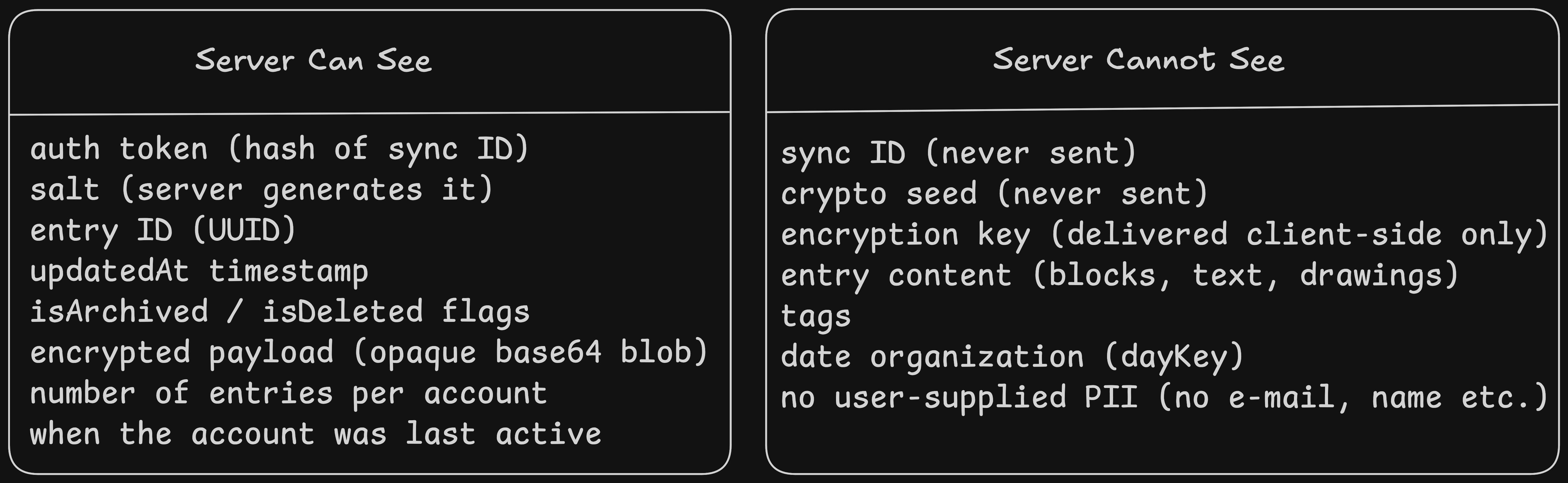

The server: what it stores, what it cannot see

The workledger-sync server is a Rust service built with Axum and SQLite. Its database schema is minimal:

-- The sync_id column stores the auth token, NOT the raw sync ID.

CREATE TABLE accounts (

sync_id TEXT PRIMARY KEY, -- auth token: SHA-256("auth:" + syncId)

salt BLOB NOT NULL, -- 16 random bytes, returned to client

created_at INTEGER NOT NULL,

last_seen_at INTEGER NOT NULL,

entry_count INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0

);

CREATE TABLE entries (

id TEXT NOT NULL,

sync_id TEXT NOT NULL REFERENCES accounts(sync_id) ON DELETE CASCADE,

updated_at INTEGER NOT NULL,

is_archived INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0,

is_deleted INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0,

encrypted_payload BLOB NOT NULL,

integrity_hash TEXT NOT NULL,

server_seq INTEGER NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (sync_id, id)

);

CREATE TABLE sync_cursors (

sync_id TEXT PRIMARY KEY REFERENCES accounts(sync_id) ON DELETE CASCADE,

next_seq INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 1

);Here is what the server knows and does not know:

Even the column named sync_id in the database is misleading — it stores the auth token, not the actual sync ID. The naming was an early decision and I have to change it to be more accurate.

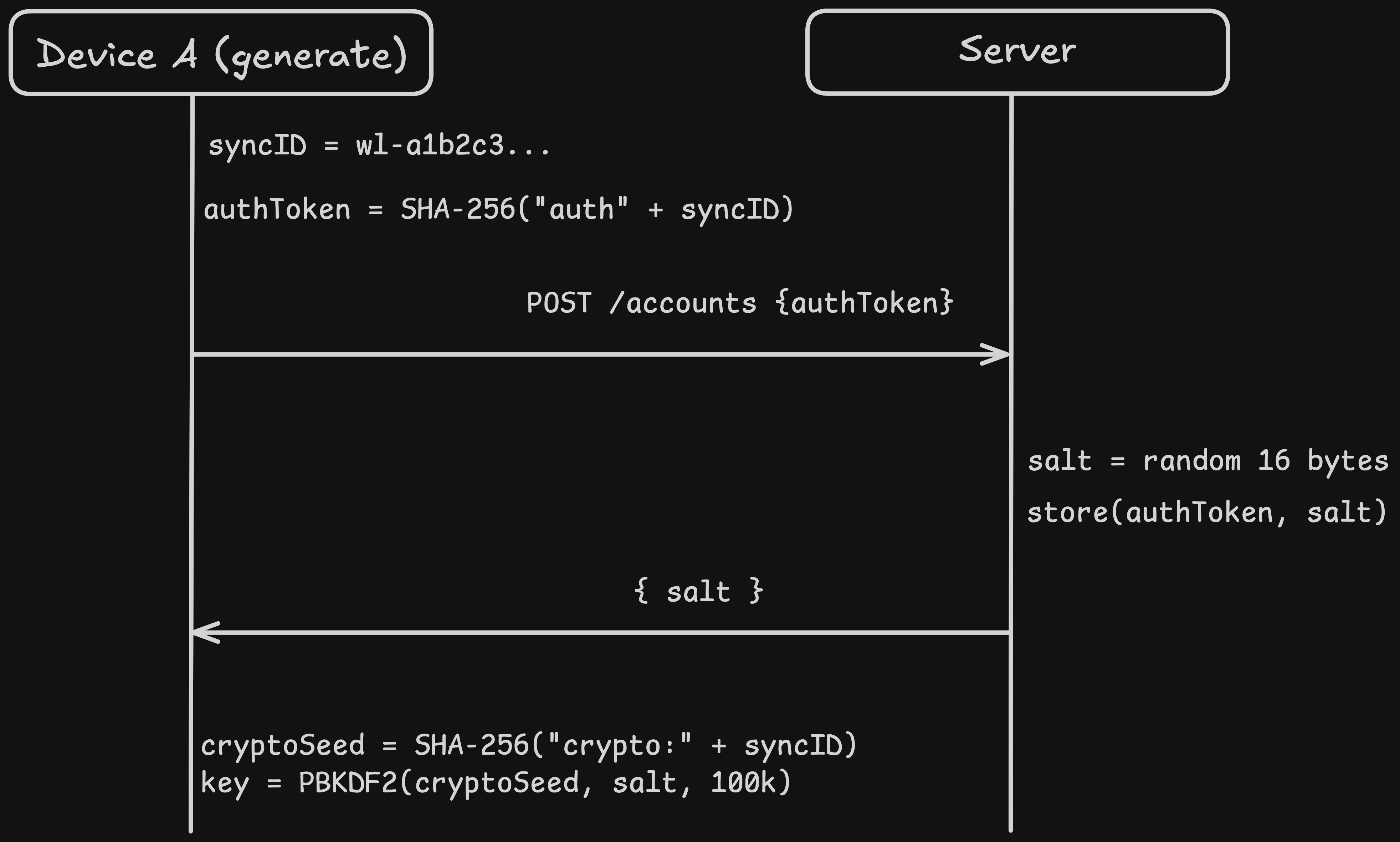

Account creation flow

When a user taps "Generate Sync ID" in the app, the following sequence happens:

- The client generates a sync ID locally:

wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0 - The client computes

SHA-256("auth:" + syncId)to get the auth token - The client sends a

POST /api/v1/accountswith the auth token in the request body - The server generates 16 random bytes as the salt, stores the auth token and salt, and returns the salt to the client

- The client computes

SHA-256("crypto:" + syncId)to get the crypto seed - The client runs PBKDF2 with the crypto seed and server salt to derive the AES-256-GCM key

- Sync is ready

The server enforces rate limiting on account creation to prevent abuse. But there is no CAPTCHA, no email verification, no OAuth flow. The auth token is self-authenticating — if you can produce it, you are the account owner.

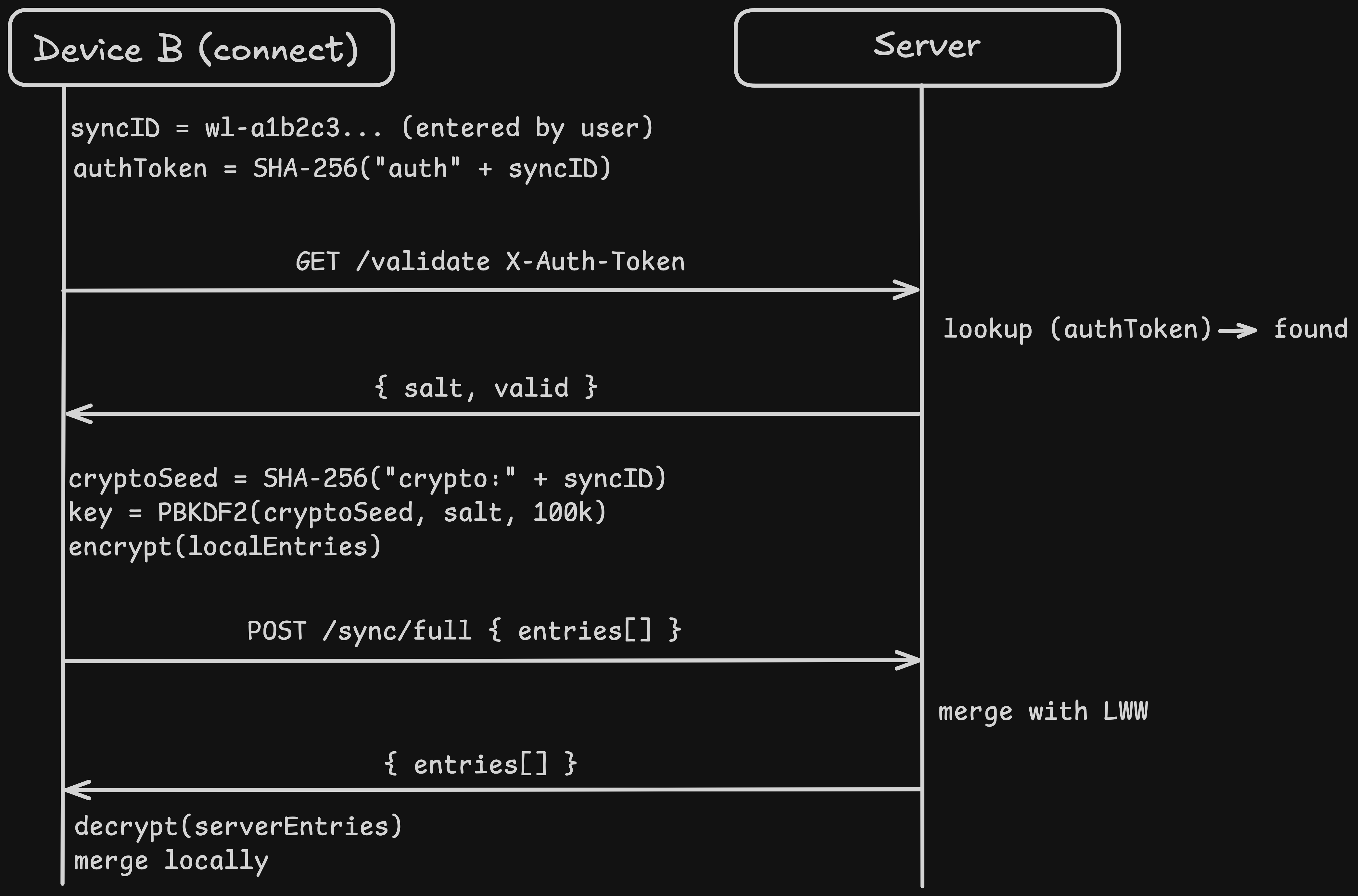

Multi-device sync

When device B enters the same sync ID, the flow is:

- The client computes the auth token from the entered sync ID

- The client calls

GET /api/v1/accounts/validatewith the auth token as anX-Auth-Tokenheader - The server looks up the auth token, confirms the account exists, and returns the salt

- The client derives the same encryption key (same sync ID + same salt = same key)

- The client performs a full bidirectional sync via

POST /api/v1/sync/full

The full sync sends all local entries (encrypted) to the server and receives all server entries back. Both sides merge using last-write-wins on the updatedAt timestamp.

This is the crucial property: because key derivation is deterministic, any device with the same sync ID and salt produces the same encryption key. The server does not coordinate key exchange. There is no key escrow. The key exists only in browser memory, derived fresh on each session.

Random questions

Going through this exercise, I had some random questions. So you might have them too:

Is SHA-256 deterministic?

Yes, absolutely. That is the entire reason this works.

SHA-256 is a deterministic hash function. The same input always produces the same output, on any device, in any browser, forever. There is no randomness involved in hashing.

So when Device B enters wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0:

Device A: SHA-256("auth:" + "wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0") → 7f3a8b...

Device B: SHA-256("auth:" + "wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0") → 7f3a8b...

^^^^^^^^

identical every time

Same input, same output. Device B sends 7f3a8b... as the X-Auth-Token header, the server looks it up, finds the account, returns the salt. Then:

Device A: SHA-256("crypto:" + "wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0") → e9c1f2...

Device B: SHA-256("crypto:" + "wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0") → e9c1f2...

^^^^^^^^

identical every time

Same crypto seed + same salt (from server) → PBKDF2 is also deterministic → same AES-256-GCM key on both devices.

The only randomness in the entire crypto pipeline is:

- The sync ID generation (once, on Device A)

- The salt generation (once, on the server)

- The IV for each encryption call (random 12 bytes every time, which is why re-encrypting the same entry produces different ciphertext)

Everything else is deterministic by design — that is what makes multi-device work without any key exchange protocol.

And why can't the server use the salt and auth token to reverse the sync ID?

Because SHA-256 is a one-way function. It only works in one direction.

"auth:" + "wl-a1b2c3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0" → SHA-256 → 7f3a8b...

There is no SHA-256-reverse function. Given 7f3a8b..., there is no mathematical operation that produces the input. This is not encryption (which is reversible with a key) — it is hashing (which destroys information). The 256-bit output is a fixed-size digest of arbitrary-length input. Many possible inputs map to the same output, so the mapping is inherently irreversible.

The salt does not help either. The salt is used later in the pipeline, in a completely separate step:

syncId

│

├── SHA-256("auth:" + syncId) → auth token ← server has this

│

└── SHA-256("crypto:" + syncId) → crypto seed ← server does NOT have this

│

└── PBKDF2(cryptoSeed, salt, 100k) → key ← salt is used HERE

The salt participates in PBKDF2 key derivation from the crypto seed, not from the auth token. The server has the auth token and the salt, but these two values never interact in the derivation chain. They are on separate branches. The salt is useless without the crypto seed, and the crypto seed is a different hash that the server never receives.

So the server would need to brute-force the sync ID: guess a value, hash it with "auth:" prefix, check if it matches the stored auth token. With 80 bits of entropy (10 random bytes), that is 2⁸⁰ ≈ 1.2 × 10²⁴ guesses. At a billion hashes per second, that takes about 38 million years.

Final thoughts

I am quite happy with how it turned out. In the beginning, everything really worked like magic. I could click on a "generate sync ID" button, it created one and started syncing immediately. I copy/pasted the same id to my other browser session, and less than a second later, I saw the same entries. This whole process made me really curious if I am ever able to implement a truly "zero-knowledge" sync someday.

And for the syncing itself: There were enough gotchas and race conditions, which I have to write another day about.